My first post of 2024 tries to answer a question I’ve been wrestling with throughout 2023.

Does China want generative AI?

Increasingly, I think the answer is: not really.

On balance, China as a whole (minus the small, elite circle of tech entrepreneurs, VCs, and AI academics) sees more risks than benefits. The government, in particular, is hedging between generative AI’s long-term potential against its short-term deflationary and destabilizing effects.

At this point, generative AI’s most tangible benefit is productivity and creativity gain for knowledge workers. Large language models and multimodal foundation models help developers write code and search documentation faster, sales and marketing professionals create slides quicker, lawyers do research better, producers make films cheaper, designers create new art faster, analysts query data easier, ordinary people search for answers quicker, and on and on. For many of these tasks, the models will get good enough soon where AI agents can do everything without any human intervention or input. Legality and industry-specific labor relations aside, for a growing economy with an inflation problem and a tight labor market, like the United States, all these benefits are highly attractive.

But of all the major economic and societal challenges facing China, generative AI fixes none of them and may make a few even worse. Let’s do this mental exercise together and steelman this position.

China's Challenges

Here is a non-exhaustive list of China’s biggest and most immediate challenges. Let’s see if generative AI is helpful in solving any of them.

A huge property bubble and debt problem from years of over construction? Nope.

Lack of social safety net for a massive aging population? Nah.

Dwindling foreign investment? Probably not.

High unemployment rate among college graduates and youth in general, most of whom aspire to be knowledge workers, not factory workers? Definitely not. Generative AI’s productivity gain may make these youths' prospects worse.

Rising tension between China and the US, especially in their technology competition? Heck no. In fact, you can argue that without ChatGPT and the ensuing AI wave, the US government would not be ratcheting up semiconductor sanctions further and expand scope into cloud services to keep Chinese companies from accessing the best GPUs, either via renting or buying.

A sagging economy teetering on deflation? Probably also a “no”. Most major technological advancements are deflationary when widely adopted, because more can be done with less. Generative AI is no different.

Social instability due to a lack of economic future? Generative AI may make things worse. It is already so good at producing fake images, videos, and voices (like Taylor Swift speaking Chinese). From a government’s perspective, the risk of viral disinformation on steroids is real; the Chinese government is not alone on this one.

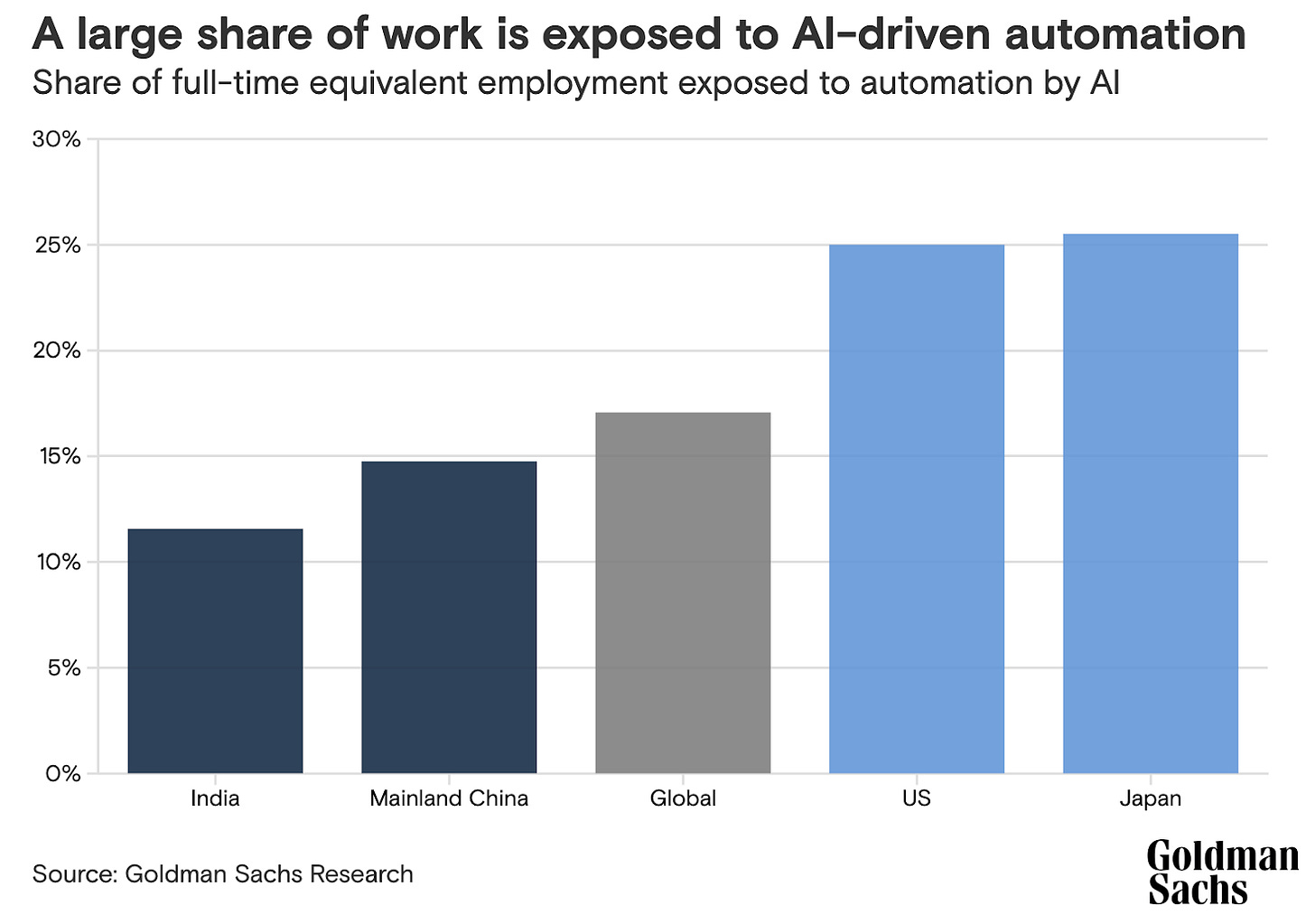

Generative AI’s risk-benefit ratio is a tricky, double-edged sword. The “oracles” at Goldman Sachs think generative AI can raise global GDP by 7%, but it can also automate 25% of labor tasks in advanced economies, like the US and Japan, and 10-20% of similar work in emerging markets, like China and India.

China does not want to miss out on that potential GDP gain. Ultimately, technology-driven productivity is crucial to the growth of a large but still middle-income economy with a vexing demographic problem, such as China’s.

But the road to realizing AI’s long-term full potential has plenty of immediate roadblocks and risks along the way. For this 2023-2024 version of China, that balance is decidedly weighted towards risks. That’s why the country’s overall attitude towards generative AI, especially its government’s, is lukewarm – a giant shrug emoji at best.

Lukewarm Attitude Towards “Soft” Tech

Rightfully or not, generative AI is classified into the “soft” tech category in the eyes of the Chinese government. And it is a category that officials have had a consistently lukewarm attitude towards. Social media, livestreaming, fintech, online education, gaming, anything that’s mostly digital and virtual are all lumped into this camp.

This “soft” refers to not only software, but also soft power.

There is an uneasy relationship between China and “soft” tech. On the one hand, the authorities recognize the efficiencies and conveniences that digital technology brings at home and the soft power accolades its top tech companies achieve abroad. On the other hand, the viral yet ephemeral nature of “soft” tech, which morphs into soft power that then influences its people’s minds makes it hard to anticipate, regulate, and control.

Gaming is a great example of this tension. China’s big gaming companies, especially Tencent, lead the world. Yet, right before Christmas, the National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA) which regulates the gaming industry released a new set of draft regulations on video games that would gut the core business model of many games, sending the stock prices of Tencent and Netease tumbling. (This is on top of the rules placed on the gaming sector in 2021 that, among other measures, limit how much time young people could spend playing games.) A few days later, the regulator struck a more conciliatory tone, stating its willingness to take in more views from industry to improve the rules before finalizing. Yesterday, the head of NPPA was fired, apparently because of the negative market reactions to the draft regulations.

Generative AI has been experiencing its own regulatory “whiplash,” from the stringent initial draft rules released last April, to the more toned down interim rules (at least on paper) announced in July, to the again more stringent and cumbersome implementation of the rules, along with additional “red teaming” requirements placed on AI model providers in October. As much as you and I may love generative AI for all its funness and usefulness, in the eyes of certain authorities, the technology is mostly digitized mathematical functions outputting digital, virtual, and mostly made-up stuff!

The way China has treated gaming and generative AI is classically lukewarm. You are allowed to exist and (kind of) grow, but don’t expect support or endorsement from the top. It’s not total hostility like the way crypto got banned. But in the eyes of the Chinese government and likely a good proportion of the Chinese population, “soft” tech growth is not quality growth. It’s risky, hard-to-control growth.

So what is quality growth? Hard tech that you can feel, touch, and show (or show off).

That means huge plants that make batteries or solar panels, factories that make electric vehicles, fabs that make semiconductors, and industrial parks that make airplanes. It is no surprise that the only product that got a shoutout in Xi Jinping’s new year address this year and last year was the C919 – China’s homemade commercial aircraft and its answer to the duopoly of Airbus and Boeing.

After his summit with POTUS during APEC last year, Xi was pleased to show off his Hongqi brand limo, China’s homemade presidential Beast, to Joe Biden. He would never show off the latest Alipay or Ernie Bot.

Is this lukewarm attitude towards generative AI short-sighted? Will it backfire? Quite possibly.

Because of the conversational, natural language interface of generative AI, anyone can access and feel its magic and potential benefits; no technical skills required. Even if some of the current capabilities are more cute and gimmicky, it does not take too much imagination to see more serious applications down the line. The field is also rapidly attracting the best technical talent and entrepreneurial energy, where all the smart kids want to work and build.

A dragged out lukewarm approach could sap organic tech entrepreneurship further, cause more brain drain, and deny China the next big economic catalyst to catapult it out of its middle-income status.

The brain drain is already happening. This global AI talent tracker from MacroPolo (h/t

) paints a clear picture of more than half of China’s undergraduate AI students leaving the motherland to do graduate work in the US and the UK, most of whom would likely stay, work and live abroad given the opportunity.Along with blocking access to platforms like Hugging Face, where developers around the world collaborate on AI projects, not only may China permanently fall behind the US in generative AI development, it is as if China wants to be. Then again, given the litany of immediate challenges sitting in front of it, China may have its reasons to be.

It is a consequential tradeoff and monumental decision that is way above the paygrade of a newsletter to judge. The best I can do is try to see things from all angles and steelman all positions.

>> Most major technological advancements are deflationary when widely adopted, because more can be done with less. Generative AI is no different.

Uhhh... no?

You're confusing micro and macro.

Microeconomically, YES, most manufactured products' prices decline over time because of economies of scale and improving technology. The classic example is the TV - a massive flat-panel screen has never been cheaper to the average family.

Macroeconomically, NO. The slow march towards cheap and ubiquitous flat-screen TVs didn't cause any kind of deflation over the last 30 years. Massive technological advances don't cause monetary deflation, they just disrupt industries. Sometimes those disruptions result in inflation, sometimes deflation, but that's a coordination-and-macroeconomic-policy problem, not a technology problem. The steam engine may have touched off massive deflationary spirals, but that was because they didn't have central banking -- in the modern era of central banking, literally no discovery (to wit, the internet, smartphones, memory foam, microchips, etc.) has triggered any similar kind of deflationary spiral. The problem was VERY obviously that we didn't have central banking, not because of technological advances.

It’s true that China doesn’t necessarily value AIGC as much as the US. It’s not only a matter of will but also a matter of ability and preferences. At the most abstract level, AIGC is but a higher-order expression of a creative, talkative culture, which China/Chinese people are not good at. Talking, making speeches, writing fancy stories are not as important to China as in the US. However, it’s true that AIGC can only achieve so much, there is still a whole bunch of other technologies to pursue. My own analogy is that: you won’t need a literature PhD to drive a truck. (Btw, the person fired is not head of NPPA though, who is a minister-level person. it’s only the head of the bureau in the 中宣部 that’s responsible for liaisoning with and managing NPPA. NPPA reports to 中宣部 now)