How to Understand Google's Gemini Delay

A high profiled reorg can take an entire year to fully settle

ICYMI: we made a major announcement last week on the future of Interconnected 2.0. Please check it out! Now on to today’s post.

The top three major cloud providers – AWS, Azure, Google Cloud – all reported their quarterly results last week. The market’s reaction was a striking divergence between rewarding Azure and AWS either their re-accelerating (Azure’s 28% year-on-year rate) or stabilizing growth (AWS’s 12% year-on-year rate), and punishing Google Cloud’s slowing growth rate (22% year-on-year rate).

(Note: “Google Cloud” includes both GCP, the cloud platform that’s more comparable to AWS and Azure, and Google Workspace, the SaaS product suites like Gmail and Google Sheets. Thus, these comparisons are not apples-to-apples, but because each of these companies frustratingly categorize and account for their cloud businesses in their own way, that is all we have to work with.)

Punishing Google Cloud just for its lack of top line growth might have been a little unfair, since it achieved a 38% growth rate during the same period last year, giving last week’s result a tougher baseline to compare with. That being said, the primary source of the market’s disappointment, in my view, is the lack of specific updates and precise timeline on the release of Gemini – Google’s multi-model foundational AI model that is supposed to be the answer to OpenAI’s GPT models. When asked about Gemini during Alphabet’s earnings call, Sundar Pichai had this to say:

“[W]e are just really laying the foundation of what I think of as the next-generation series of models we'll be launching throughout 2024.”

Vague, unambitious, and delayed until 2024. This is against a backdrop where media have reported that internally Gemini has already been deployed to some extent, externally some developers have also been given access, and a more public release is imminent. No wonder the market was surprised, disappointed, and sold off the stock!

The more interesting question is: should investors have been surprised by this delay?

No they shouldn't be. Why? One-word answer: reorg.

A tech company’s rhythm and corporate reorg’s disruptive impact of that rhythm is a dimension to investing that not many public market investors grasp, likely because very few of them have operated inside these tech companies. However, understanding reorg can hold the key to predicting when the market’s expectation is overshooting, when it’s undershooting, and investing accordingly. Let’s use Gemini as the example of the day.

Gemini: Child of a Forced Marriage

Corporate reorgs happen in the fast-moving tech industry all the time. Some are big, like a mass layoff (the term of art is reduction in force or RIF) or if a C-suite exec or a VP/senior director level leader leaves. Some are small, like if a team manager leaves. Some are driven by poor performance of a team and its leader gets fired, while others can come from a new C-suite exec joining the company and being aggressive about gathering teams underneath to grow power and influence. There’s a wide variety of scenarios that can trigger reorgs.

A small reorg usually takes one quarter to fully settle. A big reorg, like one triggered by changes at the C-level, takes at least two quarters and oftentimes an entire year to fully settle. The higher the level of change, the more cascading events occur. Regardless of the size of the reorgs, they all negatively impact people’s productivity, ability to ship products, and overall morale, as people try to figure out what to work on, who to answer to, is their promotion getting delayed, do they like their new teammates, and can they trust their new boss. Most reorgs in most companies don’t get media scrutiny, if only because they are so commonplace and mundane. But they almost always sap productive energy inside those companies.

There is no reorg that has received quite as much media attention (and market expectation) as the merging of Google Brain and DeepMind into Google DeepMind to build Gemini. The rivalry and tension between these two teams date back at least five years, if not earlier when DeepMind was first acquired by Google in 2014. Combining them is forced marriage at best, and would have not happened if OpenAI and Microsoft did not “make Google dance.” When this reorg was implemented in April, there were many clues pointing to this being one of those big reorgs that will take a full year to fully settle.

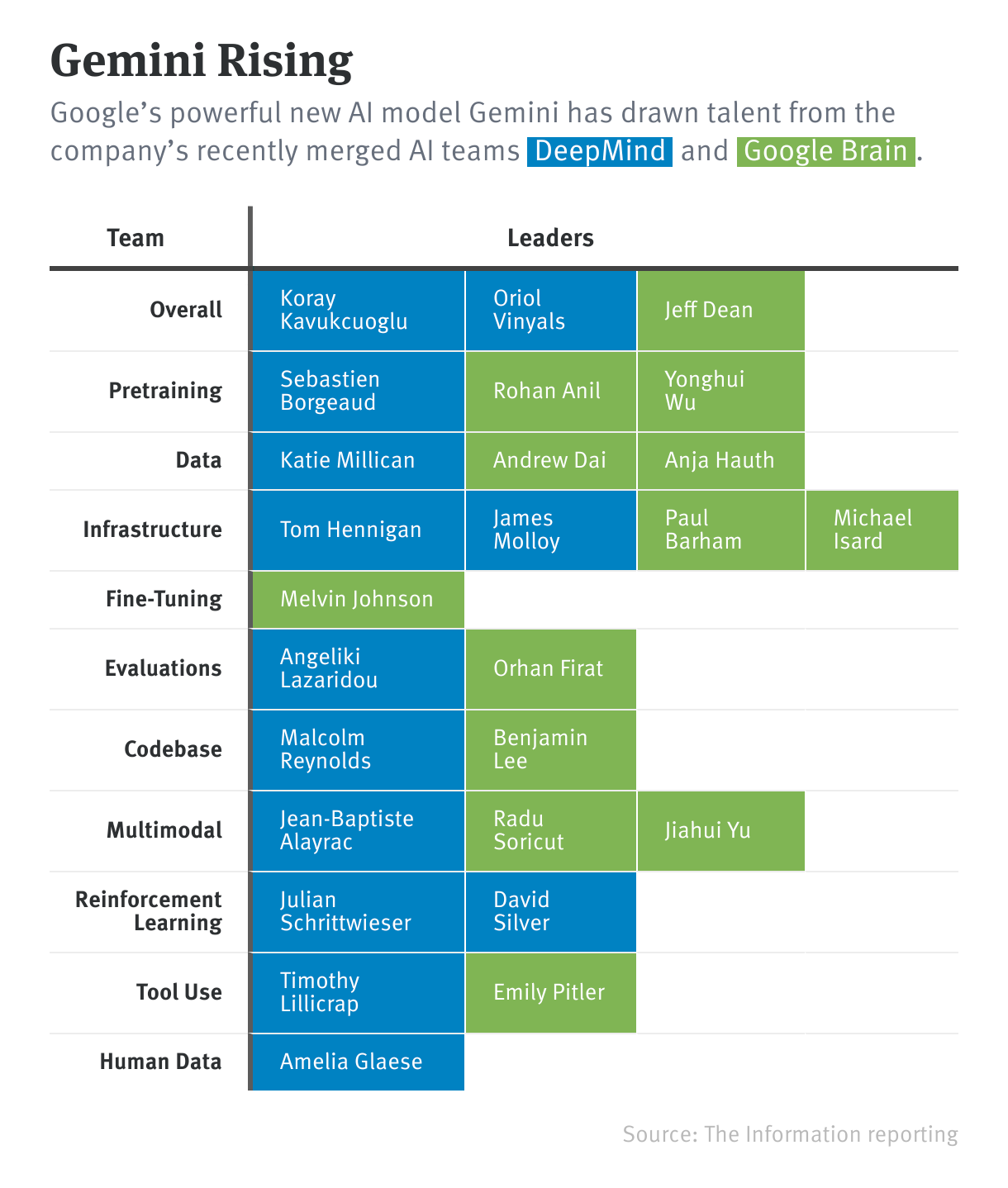

Some of those clues come from the newly combined team’s organizational structure, which The Information meticulously scouted out and described in this chart. While these charts produced by the media often have specific inaccuracies, the general impression is clear: there are many cooks in the kitchen and no clear DRIs.

In the corporate context, DRI stands for Directly Responsible Individual (not dietary reference intake). It is one of those management concepts that are more popular than they are useful, like OKR (Objectives and Key Results). What the “DRI model” prescribes is common sense: each product, project, program, or initiative should have one person responsible for its direction, execution, and outcome – the DRI. This drives accountability, clarity, and incentive alignment (a DRI should be rewarded for taking on this level of responsibility if the initiative succeeds). If you get involved in something that has more than one DRI, that’s typically bad news and a sign of dysfunction.

Google DeepMind evidently has a “more than one DRI” problem.

Yes, Demis Hassabis who founded DeepMind originally, is the single boss of this combined team and reports directly to Pichai. But inside the team, there are many DRIs mapped to most of the sub-teams, from more functional focused ones (e.g. pretraining, infrastructure) to the vaguely entitled “overall” function, which can only be understood as being responsible for overall release and success of Gemini. And these aren’t your ordinary DRIs; they are legends in the AI field for decades, like Jeff Dean (who also reports directly to Pichai). When DRIs disagree, the confusing dynamic saps a team’s productivity, alignment, and ability to ultimately ship products. That's why you shouldn’t have more than one. Sadly, Google DeepMind, as it stands today, is an example of “reorg appeasement,” where leaders from both sides get to have a say and be DRIs, so neither side’s ego gets bruised or feelings hurt.

While the DRI confusion problem is quite common, not specific to DeepMind, there are other glaring clues to this reorg being a lengthy one that are unique to each team’s culture and technical approach to building AI products.

On the people and cultural side, the Google Brain team has been more accommodating about remote work, while DeepMind has a stronger in-person working culture. This seemingly trivial difference always takes more time to mesh than outsiders expect, because it impacts each employee’s daily habits, personal life, and professional standing within the team. Additionally, Google Brain has always been more practical and product-oriented – shipping features to existing Google products like Search and Gmail to make them better (and make them money). DeepMind, on the other hand, has been more about pure research and has a stronger “ivory tower” vibe. While it is clear that the combined team needs to be more practical, ship Gemini, and compete aggressively with OpenAI and Microsoft in the market, meshing the wide divide of personalities and preferences into one focused direction is not an overnight process.

On the technology side, both teams prior to the merge have built their own custom software and tools (as talented engineers and researchers are wont to do), and maintained totally different codebases with no sharing prior to the reorg. Which side’s technology to use for what was a huge source of tension. Again, the solution was to appease both sides. This paragraph from The Information on how the technology tension was resolved says it all:

“They settled on an approach that involved using Pax, Google Brain’s software for training machine-learning models, for an early phase of model development, called pretraining. In later stages, the team used Core Model Strike, DeepMind’s software for developing models. The decision placated researchers from each group but irritated some others who didn’t want to work with unfamiliar software.”

Not only are the DRIs commingled in an awkward way, even the very codebase that underpins Google’s AI future is a salad bowl of modules and libraries that were not designed to work together, but will have to, and soon.

A codename gives off the impression of a clean start and a coherent future. But at this point, Gemini is but the child of a forced marriage that's having trouble giving birth.

Reorg Matters to Investing

The analysis I just shared are all based on publicly available information, but contextualized in my own leadership experience in tech companies – driving initiatives, managing teams, and navigating half a dozen reorgs. It’s a lens I often apply to assess if there is a mismatch between the market’s expectations and a company’s realistic capacity to deliver. Internally at Interconnected, we like to say “we can’t time the market, but we can time companies.”

Thus, considering that the Google DeepMind reorg is about six months old with high stakes, brilliant minds, and big personalities, Gemini’s delay relative to the market’s expectation is quite foreseeable. (There is another major reorg contributing to Google Cloud’s disappointing result that I won’t get into today but its effect could be similar – merging the TPU and TensorFlow engineering unit into Google Cloud.)

Not every reorg matters in the research and evaluation process of a company. But grasping the basic dynamics, timing, and aftermath of a reorg can be an important source of edge when a consequential reorg does happen and need to be closely analyzed. In the past, I have done many expert calls as the expert with investment firms and have read many transcripts of similar calls. Rarely was I ever asked about a company’s reorg and people dynamic nor do I see that line of questioning in most transcripts. It is an overlooked angle of company analysis.

As for Gemini’s future, I don’t think the pending organization issues of DeepMind will doom the project; it is simply taking longer than the market, and probably everyone inside Alphabet, has hoped. I’m sure when Gemini does see the light of day next year, it will be able to show off many incredible multi-model capabilities.

The more vexing question for Alphabet is how much will Gemini differentiate itself in the market as enterprises sprint forward with GPT, LLaMA, and even possibly Anthropic on AWS? After all, as I have postured before, models don’t make moats, they are table stakes.