Prosus: Softbank Without the Drama

Naspers's investment in Tencent yielded a more than 8000% return

“What is the single best technology investment of all time?”

An often-heard answer to this question is Softbank’s early investment in Alibaba. Indeed, Masa Son’s storied $20 million bet on Jack Ma (with his strong, shiny eyes) in 2000 has yielded Softbank a more than 4500% return. Even though, both Softbank and Alibaba are falling on hard times lately, it is hard to dispute the scale and impact of this single investment on Softbank, Alibaba, China, and arguably the entire world of tech.

However, there is one other investment that happened around the same time, also into a fledgling Chinese tech firm by a non-Chinese investor, which yielded a more than 8000% return. That story – Naspers/Prosus’s $34 million investment into Tencent in 2001 – is, however, rarely told.

Partially due to Masa Son’s dramatic, loquacious, and larger-than-life personality, the lore of the Softbank-Alibaba “marriage” is well-documented. This union continues to dominate headlines today, with Softbank’s recent selling of Alibaba’s shares to rescue its own balance sheet from the massive Vision Fund losses.

The Naspers/Prosus-Tencent “marriage”, conceived under the (much) more low-key now-ex-Naspers CEO Koos Bekker, bears both similarities to the Softbank-Alibaba investment, but also important differences and lessons – making this story uniquely worth telling on its own. More than perhaps any other single technology investment, this one illustrates the increasingly interconnected nature of global technology investing, and the impact that one home run can enable, if you have a long enough time horizon.

Naspers? Prosus? Where? Who?

One of the reasons why this story has been hard to tell is that the investor’s history, brand, and identity is kind of confusing.

Naspers? Prosus? South African? Dutch? Who?

So before we get to the heart of the story, let’s first briefly explain the corporate history and relationship of Naspers and Prosus.

Naspers is a South African media conglomerate founded in 1914. It first started as a publishing company, grew throughout the 20th century, and played a significant role in South Africa’s complicated history, including a controversial alignment with the country’s Nationalist Party that implemented apartheid.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Naspers successfully expanded into both telecom and the paid TV business. In 1994, it became a public company on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (where its shares still trade today). A few years later, under Koos Bekker’s leadership (who became CEO in 1997), Naspers sold the European portion of its paid TV business for roughly $2.2 billion dollars – seeding its war chest to expand into China, Russia, and other emerging markets at the dawn of the Internet.

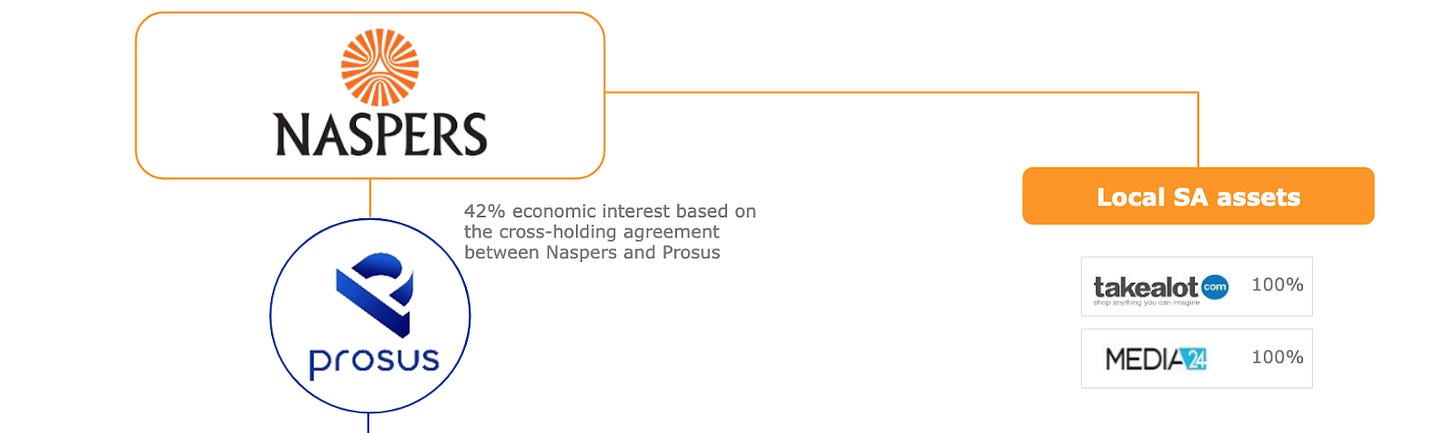

After two decades of technology investing, including China’s Tencent and Russia’s VK (formerly known as Mail.ru Group), Naspers amassed a huge portfolio of tech companies that spanned across the world. In 2019, it decided to spin out that portfolio into a separate entity called Prosus (the Latin word for “forward”) and listed it on the Euronext Amsterdam stock exchange in the Netherlands. Why list there? Likely because the Dutch has had a long history of doing international businesses, thus its exchange is more experienced in working with the cross-border accounting, taxation, and other corporate finance complexities that Prosus’s portfolio uniquely needs.

So 105 years after Naspers’s founding (and 18 years after its “marriage” with Tencent), it gave birth to Prosus – its global technology investment “baby”. As of today, Naspers holds 42% of Prosus.

Because of this rather complex history and low-key nature of both entities, the Naspers-Prosus brand is confusing and not well-known, even in the investing community and among tech founders today. (Personally, I did not pay attention to Prosus until its 2021 acquisition of Stack Overflow, a popular Q&A forum site among engineers, which I used frequently when I was a computer science student.)

In the rest of this post, for the purpose of both simplicity and (hopefully) clear writing, I will use “Naspers” and “Prosus” interchangeably, depending on the timing of the event in discussion – before 2019 will be Naspers, after 2019 will be Prosus.

“Finding” Tencent: A Mutual Rescue

Most famous investment stories are told either through the lens of an astute investor, who found a diamond in the rough due to his keen intuition, or the eyes of a tenacious founder, who convinced a powerful investor through his world-changing vision and grit. The reality is always more messy and haphazard, less straightforward and inspirational. The Naspers-Tencent story is no different.

Naspers did not find Tencent, nor did Tencent find Naspers. Instead, they found each other out of a combination of desperation and conviction that ended up rescuing each side from total failure.

In 1997, Naspers was an Internet pioneer in South Africa, having started one of the country’s first online portals called MWeb, which included messaging, blogging, email, gaming, and every product you could imagine in a web 1.0 business. But because of Africa’s tiny online population, MWeb did not succeed.

In the same year, Naspers, with its $2.2 billion windfall from selling its European paid TV business, started establishing itself in China. Its initial game plan was to leverage its technology expertise and decades of business experience to build its own Internet business. Naspers launched a series of web portals in China and invested in a few others, but they were all out-competed by home-grown leaders, like Sina, Sohu, and Netease – losing millions of dollars in the process. Naspers was getting desperate and running out of ideas.

In an almost parallel universe, Tencent, which got started in 1998 and launched QQ (a PC-based messaging service and precursor to WeChat) in 1999, was also growing desperate. QQ was wildly popular and eating up server costs like a bear coming out of hibernation. However, it had no business model and the company was running out of money. In April 2000, as the dotcom bubble began to burst in the US, Tencent managed to wrestle $2.2 million in investment from IDG and another firm, only to burn through that cash by the end of that year. Unwilling to invest more, IDG started to shop Tencent around to potential buyers to salvage what it surely thought at the time was a failed investment. Sina, Sohu, Yahoo China, and just about every sizable Chinese Internet outfit got a look at buying Tencent – and they all declined. (The common rationale was they could all build a QQ-like messenger themselves if they wanted to.)

It was at this moment of joint desperation for both Naspers and Tencent that the two companies’ paths crossed. Some accounts suggested that IDG eventually shopped the Tencent deal to Naspers when its China division, MIH, was running out of money and had barely enough funds left to make an investment. After a full year of deliberation, Naspers headquarters greenlighted the $34 million investment into Tencent. Some other accounts painted a more “romantic” encounter, where an MIH executive, David Wallerstein, kept on seeing QQ in every Internet cafe he visited in China, got intrigued, found Tencent’s office address, and went to visit the company to start negotiating an investment.

The real story is likely a combination of both tales. Given that Naspers’s Tencent investment did happen in mid-2001, it is quite possible that this investment was Naspers’s last ditch effort in China, with all of its own initiatives failing and the tech bubble bursting. Because MIH was a corporate investment arm, the year-long back and forth deliberation between the in-country team and corporate HQ in South Africa also makes sense and is typical of a corporate investment timeline and process.

That being said, the unique insight and high-level of conviction that Naspers had of Tencent should not be discounted. During this 2000-2001 timeframe, QQ’s user base was in the millions and had already surpassed the entire Internet user base of Africa. This fact may not have impressed Sina or Netease, but Naspers, with the scars of its failed MWeb venture in mind, came to China with a “prepared mind”. Seeing a 3-year-old Tencent already amassing a user base larger than its home continent with no end in sight, Naspers could care less that QQ did not have a business model, when lack of users was what doomed MWeb. This conviction, whether individually or collectively achieved inside Naspers, may also explain why Wallerstein joined Tencent in 2001 and still serves as its so-called Chief eXploration Office (CXO) today.

In more ways than one, Naspers and Tencent saved each other, via a confluence of desperation and conviction. This stands in contrast to the Softbank-Alibaba story, where neither elements were present. As documented in Sebastian Mallaby’s new chronicle of the VC industry, “The Power Law”, Masa Son got access to Alibaba in 2000, because Goldman Sachs Asia was getting cold feet about its batch of early Chinese tech investments and wanted to offload them to someone else. (This was similar to IDG’s situation with Tencent.) Back then, Masa Son’s was fresh off of his victory investing in a pre-IPO Yahoo, had capital to deploy, was not (and still is not) price sensitive, had a vague inkling that China’s Internet is booming because Cisco networking equipments were selling well there (he was on the Cisco board), thus invested in several companies that Golden offered to him, including Alibaba.

Softbank was not desperate then (though Alibaba was). Softbank also did not have the level of insight and experience operating an Internet business that Naspers had then. Masa Son, more or less, sprayed and prayed on Goldman’s China portfolio, and only Alibaba turned out to be a home run.

Holding On To A Rocketship

If the Naspers-Tencent relationship started off with a dose of desperation and luck, strong conviction and intentional long-term ownership anchored this investment for the following two decades as the Tencent rocketship took off.

Here is a brief breakdown of Naspers’s ownership stake in Tencent during the years before its IPO:

2001: 32.8% – from the first $34 million investment, acquired from Tencent’s two outside investors, IDG and Yingke

2002: 46.5% – acquired from a group of Tencent founders (except Pony Ma); Tencent founders now owned 46.3%, IDG owned 7.2%

2003: 50% - pre-IPO cap table restructuring acquired IDG’s remaining stake; Tencent founders owned the other 50%

2004 Tencent IPO: Naspers owned 37.5% immediately post-IPO; Tencent founders owned 37.5%

Naspers and the Tencent co-founders basically own the same proportion of the company throughout much of its lifetime. Due to an extraordinarily high degree of conviction and the convenient reality that these investments were made off of a corporate balance sheet with no outside investors (thus none of the pressure to sell that comes with them), Naspers did not sell a single share of Tencent for the first 14 years since the IPO. Because of its Tencent stake, Naspers was for a while the most valuable company in all of Africa in 2017 — not bad for making good use of lessons from a failed website.

Furthermore, Naspers’s stake is enhanced by Tencent’s own mastery in capital allocation and investing, beyond building WeChat, a massive gaming business, a growing advertisement business, and a cloud computing platform. Tencent’s portfolio does not only bolster the who’s who of China tech’s big winners (Pinduoduo, JD, Meituan, NIO, etc.), but also brand name American tech companies (Snap, Reddit, Epic Games, etc.), and new winners from other emerging markets (e.g. Nubank from Brazil, SEA Group from Southeast Asia).

By adding to its holding, then holding on that holding, Naspers has been compounding from a three-part flywheel: Tencent’s own growth, Tencent’s investment portfolio’s growth, funds to build Naspes’s own investment portfolio – all of which eventually became Prosus.

Naspers and Softbank are similar in this regard. Both did not sell their respective stakes in Tencent and Alibaba for a long time. Both also had the advantage of never being forced to sell, because they made the investments using their own money, not someone else’s money.

That similarity, of course, stopped when Masa Son decided to raise Vision Fund I, which did include (a lot of) outside money. To fund a portion of Vision Fund I and to buy Arm, Softbank started selling Alibaba shares in 2016, about 16 years after Masa Son saw Jack Ma’s strong, shiny eyes. Naspers held on to all of its Tencent shares until 2018, about 17 years after it wrote that first check, by selling 2% to shore up its own balance sheet and fund new opportunities, like buying Stack Overflow for $1.8 billion and capitalizing its venture arm, Prosus Ventures.

This year, both companies announced more selling of their shares, albeit in very different fashion.

Hitting Rough Times

As the global macro economic environment deteriorates, Softbank, Prosus, and every company that invests in technology is feeling the pain. In his usual dramatic way, Masa Son announced Softbank’s vomit-inducing quarterly loss of $24.5 billion last month with a portrait of Japan’s first shogun, to show both his desire to repent for his mistakes and his courage to come back victorious. To make up for all the losses in the meantime, he plans to sell more Alibaba shares. The drama dominated headlines for days, which I discussed in a previous post.

A couple of months earlier, in June, Prosus also announced more selling of its Tencent shares to keep improving its balance sheet, fund share buybacks, and boost its financial position during a tough, uncertain time. As the “Softbank without the drama”, Prosus made its announcement in a typically boring earnings press release.

Softbank is likely in a more dire state, having taken huge outside investments from Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi to fuel Vision Fund I, which took big swings at Uber, Didi, and WeWork – all of which are bad judgments that Masa Son has publicly admitted. Its portfolio of private companies will follow suit with valuation write-downs later this year.

Having taken no outside money, Prosus’s more quiet, conservative approach puts it in a better position to weather the storm. This is not to say that Prosus’s future is any more easy or certain than Softbank’s. Because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Prosus had to write off its 27.29% stake in VK, worth roughly $760 million. Tencent’s stock price has dropped more than 60% since its February 2021 peak. Its global investment portfolio is also facing double scrutiny, from Chinese regulators for antitrust reasons and US regulators for geopolitical concerns.

However, Prosus Ventures has continued to pour money into fast-growing tech companies in emerging markets. Notably, during its most recent fiscal year, out of the $900 million worth of investment it made, $800 million went to startups in India.

Here is a picture of the Prosus portfolio based on its recent earnings release:

Prosus now sports an enviable portfolio of public and private tech companies comparable to Softbank’s – spanning an interconnected set of categories, including classified, fintech, delivery, edtech, blockchain, and more. This is made possible largely because of that $34 million dollar check it wrote to Tencent 21 years ago and the steady, shrewd, and long-term shareholder behavior it displayed since – no drama, no fanfare.

Both Softbank’s high-profile style and Prosus’s low-key approach have their own benefits and drawbacks. Both will likely never change their respective ways. It will no doubt be interesting to see who will do better in the future. But we probably all know whose story will always get told more, regardless of the result.