When the Houthis Found “the Cloud"

More than 20 countries are, in one way or another, involved in the four damaged undersea cables.

One topic this newsletter has been obsessed with over the last four years is cloud data centers. Partially because of my previous industry experience, working deeply on cloud-based tech products, partially because these data centers are just fascinating and so crucial to the global digital economy yet so misunderstood, I have always felt the need to write every time something interesting about “the cloud” comes up.

This obsession took an interesting turn when, last week, the AP reported that the Houthis slashed four (not three, as the headline suggested) undersea data center cables buried in the depth of the Red Sea. If true, then the Houthis have just found “the cloud” and realized how much disruption damaging these cables can cause to the global economy, perhaps even more damaging than their attacks on all the ships.

These four cables, together, carry roughly 25% of all the data traffic that goes through the Red Sea. All the cables under the Red Sea carry roughly 80% of the traffic that goes westward from Asia – which amounts to roughly 15% of all Asia traffic (the rest, presumably, goes eastward under the Pacific). So that is about 3% (0.15 * 0.8 * 0.25) of the entire traffic volume from Asia. This may look like a small number, but considering that the APAC region has 2.6 billion online users, one-third of humanity, this 3% corresponds to roughly 78 million people. Not a small number.

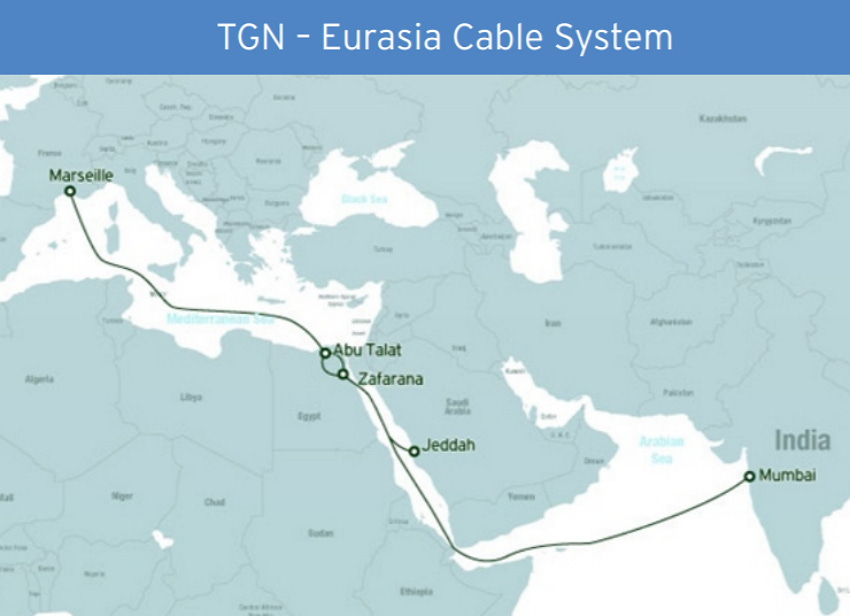

What’s more interesting is the geopolitical implications. Most of the cables that connect all the data centers, which make up “the cloud,” are owned and operated by a consortium of large telecom companies or large tech companies that want their own cloud computing infrastructures (e.g. Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Google, Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei, etc.) More than 20 countries are, in one way or another, involved in the four damaged undersea cables – TGN-EA, AAE-1, EIG, SEACOM – either directly via state-owned telco’s or indirectly through private companies or investment vehicles within their jurisdiction.

Let’s take a closer look at who these companies (and countries) are.

Who Owns What?

Below is a list of the consortia behind each of the four damaged cables, sourced from the wonderfully informative website, Submarine Cable Networks.

TGN-EA (Tata Global Network - Eurasia):

Tata Communications (India)

Bahrain Internet Exchange

Ooredoo (Qatar and Oman)

Mobily (Saudi Arabia)

Etisalat (United Arab Emirates)

Telecom Egypt

British Telecom

China Unicom

Chuan Wei (Cambodia)

Djibouti Telecom

Etisalat (United Arab Emirates)

HKT – PCCW Global (Hong Kong)

Mobily (Saudi Arabia)

Omantel (Oman)

Ooredoo (Qatar)

PTCL (Pakistan)

Telecom Egypt

Telecom Yemen

Vittel (France)

OTEG (Greece)

Reliance Jio (India)

Time.com (Malaysia)

TOT (Thailand)

AT&T (US)

Bharti Airtel (India)

BSNL (India)

BT (UK)

Djibouti Telecom

du (United Arab Emirates)

Gibtelecom (UK)

Libya International Telecommunications Company

MTN (South Africa)

Omantel (Oman)

Portugal Telecom

Saudi Telecom

Telecom Egypt

Telkom South Africa

Verizon (US)

Vodafone (UK)

Industrial Promotion Services (Kenya)

Remgro (South Africa)

Sanlam (South Africa)

Convergence Partners (South Africa)

Brian Herlihy (CEO of Endeavor Energy)

More than 20 countries involved in four out of more than 15 such cables under the Red Sea – a narrow body of water that has become a single point of failure, not just for global shipping, but also for global data center connectivity.

Let that sink in… (Pun absolutely intended)

Hong Kong at the Center

It’s not clear yet how these cables were cut. And, so far, the Houthis have not claimed responsibility (or credit) for these damages, though there were signs of their intentions (i.e. in the group’s Telegram chat room) leading up to the cable cutting on Leap Day (February 29).

Amidst all the attacks above and below water still happening in the Red Sea, the only source of reliable information on these data center cable damages comes from a Hong Kong company, HGC Global Communications, a digital infrastructure operator and broadband provider that happens to be at the center of it all.

Through two concise, matter-of-fact statements, HGC shared the extent and significance of the damage, as well as what it did to re-route traffic and keep services online for its customers. The re-routing is quite interesting. Some of the traffic was diverted to the other 11 undamaged cables still under the Red Sea. Some moved eastbound through the US and then to Europe – the long way. And some traffic actually went through Mainland China via land cables to make its way eventually to Europe.

If you are as sensitive as I am about these issues, a traffic diversion through Mainland China may set off some red flags, even though this is obviously a case of trying to fix an “exceptionally rare” emergency situation, not an intentional act of malfeasance. Perhaps aware of this dimension, HGC made a pointed effort in its statement to remind people that it is a company “dedicated to upholding Hong Kong's position as an international telecommunications hub.”

All this simply shows despite the omnipresent “cloud,” made only more powerful by all the AI-focused GPUs going into them, it is a fragile network connected by cables that are vulnerable to their physical surroundings. They can be damaged by natural disasters, like the Taiwan earthquakes in 2006. They can be cut by anchors of large ships, as was the case in 2023, when a Russian fiber optic cable was severed under the Baltic Sea when a Chinese container ship dragged its anchor along the seafloor. Or they can be slashed by a terrorist organization. The Red Sea, being relatively shallow and narrow compared to most other “sea’s”, is especially vulnerable to this “drag and cut” maneuver, whether accidentally or intentionally.

I’m not predicting a proliferation of sabotage of undersea cloud data center cables – most bodies of water where these cables are installed are far too expansive for these attacks to make sense. But the next time Netflix is down, I would be wondering: are rats chewing off networking cables in Northern Virginia again or is this a terrorist attack?

Makes one think that the undersea high voltage power cables are also vulnerable. These often run at 500,000 volts and carry 2+ gigawatts. They may be better armored though I have no particular knowledge.

They are very common in the North Sea and Mediterranean..

Reynolds shadow banned me on his site. Of course the reason is secret but as near as I can tell from who did and didn't get banned, I think the problem is that I made an an issue about his connection with Salem Media.