Is JD Cloud the New “National Champion”?

The "national champion" label commands more market power in an age of deglobalization and constant sanctioning risks.

JD Cloud is quietly, but effectively, positioning itself as the new “national champion” in China’s cloud computing market. This move became apparent when, during the weeklong “Two Meetings” deliberation that anointed China’s leaders of the next five years, JD Cloud’s top executive, Cao Peng, was the one who delivered a set of proposals on how the country can accelerate the modernization and digitization of its supply chain on the cloud with 100% domestic technologies.

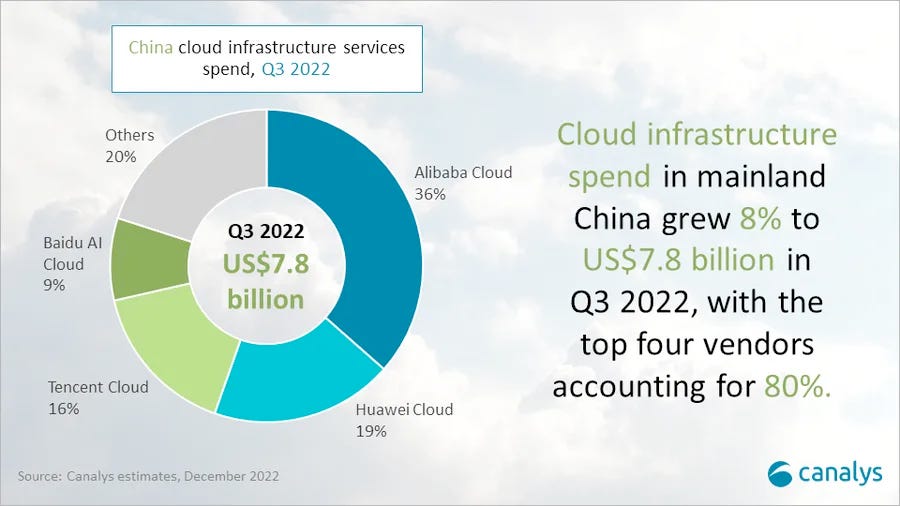

JD Cloud is a minor player in China’s cloud industry. So minor that the government's own think tank, China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, hardly mentioned JD’s name in its official white paper, which I analyzed in-depth a few months ago. Industry analysts feel the same way. In Canalys’s latest estimates of China’s cloud market, JD Cloud doesn’t even get a sliver on the pie chart.

Thus, it’s extra notable that it was JD Cloud’s executive of all the Chinese clouds, who had a voice during the all-important “Two Meetings.” It also helps that Cao Peng is a member of the National Committee of the People's Political Consultative Conference.

Yesterday, JD held a “JD Cloud Summit” in Guangzhou to further amplify the messaging of its proposal and, not surprisingly, touted why JD Cloud should be the go-to cloud platform to use. What emerged from JD’s proposal and its event, which Cao Peng also spoke at length, are two new slogans that illustrate both the progress and struggle that China’s facing in completely switching its digital infrastructure from foreign to domestic technologies – and two opportunities JD Cloud hopes to capitalize on.

Slogan 1: Real Replacement, Real Usage (“真替真用”)

This slogan shows that, despite all the calls-to-action to switch to “Made in China” technologies, made more urgent by the US’s increasingly tighter export control, companies still don’t trust domestic technologies enough to use them for real.

This struggle was explained in more detail by the plain-spoken Cao, who shared that most companies are willing to try homegrown technologies in the development and testing stage, but not in production (or real usage).

For readers who are not familiar with how companies adopt new technologies, the “development to testing to production” migration process is typical. If you are a large company and/or a less technically capable company, the process can often take one to two years, depending on the level of urgency, technical sophistication, and dedicated engineering resources. Companies will usually create a development environment to “play around” with the new technologies, and if all goes well, test it in a staging environment that simulates the real world to “kick the tires” further. Passing the threshold from “testing” to “production”, which basically means deploying the technology into the wild, is very hard. There is always a chance that new technologies could cause issues, interrupt business operations, and lose revenue or customers. Rolling back an in-production deployment is also difficult and messy. Even if all goes well, it is best practice to keep your previous technology stack around for a while as a failsafe.

By coming up with this slogan as a key message, it signals that even with all the urgency from the top and pressure from the outside, most companies don’t yet trust domestic technologies enough to put them in production and risk business losses. This fear is understandable, because most domestic technologies are unproven and most businesses are trying to recover from Zero Covid and don’t want to add another risk to their operations. Meanwhile, the risk of not being able to, say procure the latest Nvidia GPUs, is more remote and can be circumvented rather easily than US regulators care to admit.

To inject more confidence into domestic technologies and position itself as the “national champion”, JD shared that 80% of its own workloads now run on “Made in China”' solutions. Companies who are slow to make the foreign-to-domestic switch can leverage JD’s experience – all distilled and packaged into a platform called JD Cloud. It is perhaps not lost on JD’s audience, and certainly not to the sharp readers of this newsletter, that even the “national champion” is only at 80% and not 100%.

Slogan 2: Multi-Cloud, Multi-Silicon, Multi-Workload (“多云多芯多活”)

If slogan 1 speaks directly to China’s overall challenges in adopting domestic technologies, slogan 2 sounds more self-interested – tailored to benefit JD Cloud. It is pushing a multi-cloud narrative that commonly benefits the smaller players. (That’s why AWS, as the longtime global cloud computing leader, would not allow even the utterance of the word “multi-cloud” at its Reinvent conference a few years ago. It relented in more recent years, when ignoring multi-cloud became impractical and tone deaf.)

As a small player, JD Cloud benefits from a “multi-cloud” industry landscape. As the “national champion”, JD Cloud embraces a comprehensive menu of domestic chips (“multi-silicon”) and homegrown infrastructure software products to handle all types of use cases (“multi-workload”), so customers can (in theory) use a high-performance cloud that uses 100% “Made in China” solutions from top to bottom.

How comprehensive? This infographic, aggressively promoted by JD, shows all the components of an entirely homegrown digital infrastructure that makes up JD Cloud.

What is noteworthy about this infographic (and you don’t really need to read Chinese to appreciate it) is that it goes into painstaking detail to highlight and squeeze in every homegrown product worth mentioning in the cloud computing stack. JD Cloud claims to integrate them all, starting from the CPUs/GPUs and operating systems layer, to the IaaS and PaaS layer, to even the SaaS layer that includes collaboration products, like Google Doc, and virtual meeting tools, like Zoom. The stack also includes open source projects created by Chinese companies, like TiDB (by PingCAP) and OpenEuler (by Huawei).

If you take this infographic at face value, there already appears to be multiple “Made in China” alternatives in every layer of the cloud. In theory, all the pieces of a 100% domestic cloud are already in place. Of course, where the rubber meets the road is how well these solutions work in production, not just individually but together in a single, coherent cloud platform. That’s the challenge. And that’s the problem where JD Cloud, poised to be at the center of a multi-cloud, multi-silicon (domestic silicon, of course) world, is positioning itself to solve.

Can JD Execute Better This Time?

It has always been perplexing to me why JD is not more of a leader in the cloud. It is not because JD lacks technical prowess or innovative capabilities. In fact, JD was an early adopter in a lot of cutting edge tech that has now become mainstream. Back in 2018, JD was an early user of Kubernetes, a now-ubiquitous cloud container orchestration software that popularized the notion of multi-cloud. For a while, JD managed the largest Kubernetes cluster in the world! However, JD was slow to package its cloud capabilities into products to meet market demands.

While JD Cloud was late to the market, China’s fast-growing (though recently slowing) cloud sector has been carved out by other big players, each with its own lanes. AliCloud, the market leader, serves SMBs and startups well and is moving up into large enterprises. Tencent Cloud caters to social and gaming products, not surprising given that those verticals are also where its own core products shine. Huawei Cloud is a strong fit for the public sector and state-owned enterprises, given its longstanding roots and relationships with those sectors. Baidu is trying its damn hardest to carve out an “AI lane” for itself (see my previous writing on Baidu and AI). ByteDance Cloud, a new entrant, is squeezing into the space by packaging its own powerful recommendation engines as a cloud to lure companies who aspire to be like ByteDance one day.

Where does that leave JD Cloud? Well, beyond being an e-commerce juggernaut, JD does have differentiating capabilities in managing a complex and highly-efficient set of warehousing, delivery, and supply chain operations. These capabilities are “infrastructural” by nature, thus are amenable to be packaged into cloud services, which is, at the end of the day, just digital infrastructure for rent. Now that it is hard-pivoting into its role as a “national champion” – a label that commands more market power in an age of deglobalization and constant sanctioning risks – JD Cloud may be getting a second chance.

Coming out of the “Two Meetings”, JD clearly has the ear, if not the backing, of the newly-anointed government leaders and will play a key role in China’s next phase of digitization. Given the challenges ahead, especially as encapsulated in “Real Replacement, Real Usage”, JD Cloud must deliver a solid, enterprise-level cloud experience without foreign technologies or it will risk embarrassing itself and China’s entire push to adopt domestic technologies.

The Spiderman rule applies to all. Being a “national champion” comes with both great power and great responsibility.

This is a fairly interesting topic as JD.com has diversified into healthcare in a very significant way.